Wildlife Monitoring in the Osa Peninsula

told by Katie (Resident Biologist from the University of Cambridge) and Chantelle (owner of Golfo Dulce Retreat)

Here at Golfo Dulce Retreat we are lucky to be surrounded by thousands of acres of pristine lowland tropical rainforest and one of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world. But a healthy rainforest, one where apex predators coexist along with prey species, hides its animals well. Although it is not uncommon to meet large troops of squirrel monkeys during a hike through the rainforest, together with many species of birds, the occasional solitary tamandua and an infinitesimal amount of different insects, your chances of seeing a puma, quite frankly, are pretty slim. But we knew that all sorts of wildlife was out there. We kept finding large footprints on mud banks, deep scratches on the bark of trees, and even skeletons of recently-killed collared peccaries, smaller mammals, a large brocket deer even.

Finally, in December 2019, we summoned the help of the Osa Conservation camera trap specialists. Osa Conservation, a small - but impactful - non profit organisation based on the Osa Peninsula across the Golfo Dulce, had in recent years been building a large network of camera traps throughout the Osa region, in order to assess the status of top predators across world-known Corcovado National Park, through the biological corridor that connects it to Piedras Blancas National Park - at our backdoor - and higher up to the largest remaining tract of lowland tropical rainforest in Central America in La Amistad International Park.

Hence, we thought Osa Conservation Researcher, Daisy, and Wildlife Manager Eleonor would be just the people we needed to start up our own camera trap network… and the results have been more spectacular than we could have ever imagined!

SETTING UP AND MONITORING CAMERA TRAPS

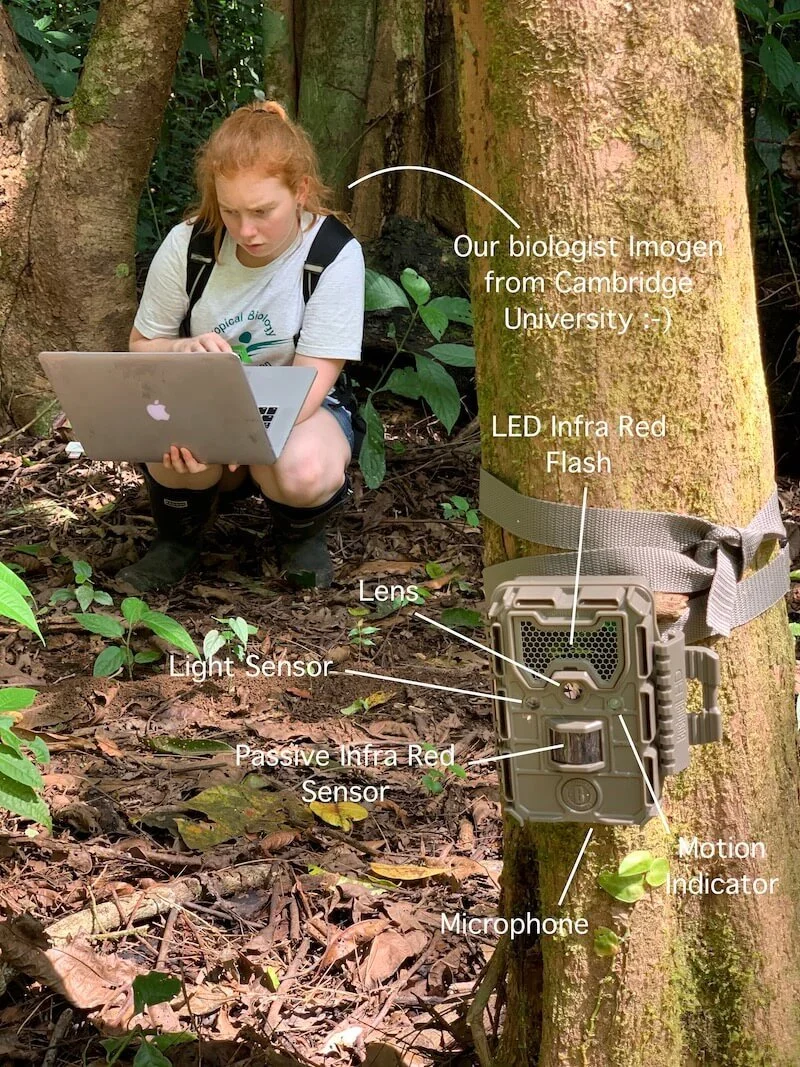

If you aren't familiar, camera traps are inconspicuous video cameras that are activated remotely by a motion sensor. As an animal passes in front of the camera, a short video clip is recorded on a removable SD card. Camera traps are invaluable tools for conservationists and scientists to monitor wildlife populations and study the behaviour and ecology of animals in a natural setting.

Our resident biologist Imogen from Cambridge University retrieves data from a camera trap strapped to a tree in the rainforest

With the choice of thousands of potential trees and locations to place our camera traps, choosing the perfect spot was no easy task. Thankfully we had our local rainforest guide, Agostine, to assist us with this. After years of trekking the rainforest of Piedras Blancas National Park and the wider Osa Peninsula, Agostine had some ideas as to where we may get interesting sightings. We eventually settled on three locations: a mud bath, a fallen tree and a network of underground burrows. Each week, our resident biologists expectantly ventured into the forest to retrieve the video footage. As more data was collected through the passing weeks and months, our surrounding rainforest became truly alive with an array of wildlife which, unhindered by human presence, went about its daily and night life displaying complex behaviours of interaction: scent marking, grooming, foraging, food storing and often, simply playing.

Our rainforest guide Agostine looks for a site for a camera trap

Wildlife Manager Eleonor Flatt from Osa Conservation helps installing a camera trap at our waterfall

THE RESULTS

The Peccary Mud Bath

The mud bath on our self-guided Giant Ceiba trail is now fondly known as the 'Peccary Mud Bath' after our camera trap revealed hundreds of endearing videos of these creatures frolicking and cooling off in the mud. However, it appears that peccaries aren't the only animals which enjoy this spot. We have footage of agoutis, armadillos, ocelots and pumas - both juveniles and adults - visiting the mud bath to drink and forage. Birds can often be seen drinking and bathing there: tinamous, wood rails, doves, quails, hawks, falcons and more.

But perhaps the most surprising and exciting sighting that has come out of this camera trap is the greater grison. The greater grison, which is a member of the weasel family, is something of a mystery in the local area as despite its healthy population size, it is seldom seen. One researcher spent months setting camera traps in Costa Rica to observe this species and did not get a single viewing in over 60,000 hours of footage. Due to the difficulty in observing these creatures, little is known about their ecology and natural history. We were therefore incredibly excited to find two videos of greater grisons on our camera trap. As footage of greater grisons keeps coming in, we are pretty confident that a stable population of this mysterious species definitely inhabits our surrounding forest.

A group of peccaries stop at our rainforest wallow

Two greater grisons are spotted at the mud bath!

The Fallen Tree Across our Dry River Bed

Fallen trees offer an excellent opportunity for wildlife to cross rivers, as they create natural bridges. Our quebrada, as a small river bed is locally called, stays mostly dry but can fill within minutes with muddy waters and tumbling rocks during heavy afternoon downpours. So we were expecting the local wildlife to be using a fallen gallinazo tree for easy crossing, and a camera trap was placed nearby with the hopes of capturing this. The footage did not disappoint, and we have witnessed a plethora of animals including ocelots, tayras and tamanduas (anteaters) crossing the trunk. Coatis are often seen lifting the decaying bark in search for insects - male adults always on their own, while females are seen hurrying across the log surrounded by many other females - probably their sisters and cousins who knows - and their young.

A slightly more unexpected surprise was when we captured the puma, the rainforest's second largest predator behind the jaguar, trailing the quebrada below our camera.

A puma walks along our dry river bed

A troop of female and juvenile coatis use a large fallen tree to cross our dry river bed

The Underground Burrows

Nestled deep into the primary rainforest, we were intrigued as to what could be living inside a large network of underground burrows. While the occupants (if any) of these burrows remain a mystery, our footage has revealed that this area is particularly popular with the nine-banded armadillo. As time went by, different species were also observed: the nocturnal paca, a large rodent whose highly-prized meat makes it very vulnerable to hunting in many parts of Central America; red-tailed squirrels, hog-nosed skunks, common opossums and many other small mammals. But we were mainly overwhelmed by videos of armadillos scampering through the rainforest grounds, so it was finally decided to move this camera trap to another location. As luck would have it, that’s when two curious pumas walk across the field of view of our camera trap!

A large puma checks the entrance of a burrow at this camera trap site

Pacas are generally only found in places where no illegal hunting occurs as their meat is highly prized

One of the hundreds of footage of a nine-banded armadillo scurrying around the rainforest floor

We have been so overwhelmed and inspired by the results of our camera trap project so far, and dedicate a lot of our time and effort to continuously extending it with the installation of new cameras (and replacement of not-so-old ones.…nothing lasts long here and waterproof IP ratings were never properly tested in a rainforest we reckon!). We are extremely grateful for the help of Osa Conservation as well as the amazing support we have been receiving by our guests, some of whom have generously contributed to our project and gifted us with new camera traps.

THE PROJECT LIVES ON

On the back of these great results, we decided to turn this project into a permanent programme, consisting of eight camera traps monitoring wildlife throughout our vast property, 24/7. Our data is shared with Osa Conservation in their yearly survey of wildlife in the Osa Peninsula, with the aim of better understand the ecology of Osa’s wildlife and make informed decisions for long-term environmental management needs. If you haven’t already done so, you can watch two videos of some of our best findings below.